And so to ETSI*, the august telecommunication standards body in Sophia Antipolis. I was kindly invited to by BT's Keith Dickerson and ETSI's Margot Dor to present during a board meeting session entitled "Hell's Kitchen: IMS and Web 2.0 Compete or Complete?" — an attempt to provoke fruitful discussion ahead of defining strategy for topics which included The Web and open source. I was encouraged to adopt a rather provocative position, one in which I was clearly representing open source and The Web and not necessarily a formal position from my employer. Oh my!

For those innocent in the ways of the telco, I'd position ETSI as a place where large companies, operators, vendors and regulators coalesce, publishing large rock-solid specifications for communications. Mostly these are things which most of the planet uses every day: SMS being a prime example, a small part of the enormous GSM which when printed is a foot or so high and yet just works. Web developers can learn a lot from organisations whose outputs are so solidly interoperable and deemed trustworthy enough to be used as inputs to legislature. But I wasn't here to praise The Romans and their functional viaducts. I was here to warn them about the Web 2.0 Vandals amassing outside!

Recently a significant part of ETSI's focus has been on something called IMS. I'm willing to wager few ordinary IT folk have heard of IMS, but for many in the telco industry it's a big bet, one predicated on being able to exploit the strong relationship between a punter and their operator. IMS aims to build an IP based multimedia platform from which vendors and vested interests will be able to innovate. I'm no fan of IMS, a prejudice re-enforced by hearing use-cases which sound like water companies standardising how to pipe around coffee and soup. That along with being someone who advocated BT's Web21C SDK eschewing Parlay-X, gave me a strong sense of putting my head inside the lion's mouth.

The session started with polite, understated views, mainly from the IMS perspective, from TISPAN chair Rainer Münch of Alcatel-Lucent "IMS needs to engage the Web 2.0 community" and OMA Technical Plenary Chair Mark Cataldo of France Telecom/Orange: "our standards need to emerge quickly to remain relevant". This was followed by Vince Pizzica of Thomson, the company who invented mp3 and a myriad of other technologies the likes of Apple have innovated upon to great effect, capturing a mass-market not so much by great engineering, but rather through great design, marketing and service. I particularly enjoyed his observation that there are plenty of more profitable sectors for a technology vendor than conventional telecoms!

All good stuff, but it was Roland Montagne who really piqued my interest in a great presentation around broadband adoption and observations from rolling out fibre to the home (FTTH). Experience from trials of fiber in Hong Kong has revealed people tend to upload more data than they download, which is in direct conflict to the premise of ADSL. It's a vision I've heard Kevin Marks and JP postulate many times, so great to see it's coming true! I was therefore amazed to hear someone joke: "if everybody's uploading more than they download, what happens to all the packets?" as if data was subject to double entry bookkeeping, or there was a law of data entropy: packets cannot be created nor destroyed! This made me realise not everyone is on the same page, anticipating a world of people uploading high definition home movies, streaming telemetry data to aggregation services, hosting video conferencing and participating in peer-to-peer data sharing such as a distributed cloud, along with a multitude of other innovations only possible in a symmetrically connected world. I was reminded of the old, apocryphal quote from a Kodak executive dismissing digital cameras and their poor quality with "people love photos", when in reality it's the taking of photos that people love. Sometimes it's hard for an incumbent with large sunk costs and a vested interest in business as usual to foresee and embrace change. Indeed for a telco or large commercial software vendor the best way to predict the future is to prevent it.

So the pitch was prepared for this web kitteh to take the stage — herein an attempted explanation the selection of my usual slides assembled to accompany this talk:

My background is in communications, by which I mean data integration for large companies. A while ago I found myself representing BT at the W3C in the area of Web services. If you're lucky, you will never have heard of Web services, a manifestation of Service Oriented Architecture, snake-oil devised to further the dependency of organisations on vendors and their tools.

Web services, not to be confused with The Web, evolved through privileged people in smoke filled rooms writing specifications which they then attempted to rubber-stamp in a number of different consortia.

A tennis circus of standards representatives were then dispatched to trot the globe, competing and resolving the same issues in different ways in different working groups. The result was a raft of incompatible specifications which at best were incoherent.

Nothing but the simplest of scenarios worked, so they formed the Web Services Interoperability Organization to write profiles removing the more esoteric features and to email corrections to themselves, elsewhere. Seven years later, and some of the simplest use-cases interoperate across a handful of toolkits. Sometimes.

My take from participating in this process was that stanardization is really hard, but such an approach to standardization comes directly from a time when vendors ruled the earth, and IT strategy was mostly a matter of reading the runes of vendor roadmaps and trying to divine the lowest common denominator. Those days are over, in no small part thanks culturally to open source and architecturally to this thing called The Web.

After a few years of hand-waving about the WS-Emperor being chilly, I decided I was ineffectual in my supposed role as BT's Chief Web Services Architect and failing in my self-appointed role as a Moral Compass, and maybe it was time to move on.

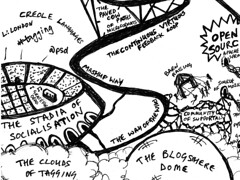

Lucky for me BT bought a small company Osmosoft, a team of impassioned developers who articulate the values of The Web, developing innovative collaborative tools, such as TiddlyWiki, with the express purpose of fostering innovation through open source. On joining the team Jeremy Ruston encouraged me to produce a poster explaining my experiences with the Web and Web Services. The result was a doodle: The Web is Agreement, which you may or may not find useful!

When I mentioned ETSI to my colleagues, I was surprised by their positive reaction. One enthused how he visited their site most everyday, another that a friend of his girlfriend actually used them to make a modest living. It was then I realised we were talking about etsy.com a Web 2.0 arts and crafts marketplace.

On explaining what ETSI actually was, I was met with a stony response. Yes, I was headed to The Ministry of Telco, and I had their sympathy!

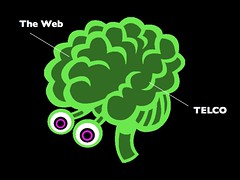

You see I think there is a real difference in how Web and traditional Telco people see the world, and it's about freedom and acceptable points of control.

Now I'm all for defending the solidness of GSM, and how 3G is changing people's lives. An eight hour battery life and mobile broadband means I can work anywhere, but to use my 3G dongle when traveling to France costs an eye-watering £3 a megabyte! My mobile phone, which even if I were allowed to tether to my notebook, has similarly punative roaming costs. So I opened my laptop in Nice airport for a spot of Wifi. Only instead of being greeted by the usual Safari "Top Sites" panel, I was faced with a parade of pages from a WiFi paywall demanding my credit card for €6 an hour. I suspect this man in the middle attack now has a nice collection of most of my private session cookies.

I've heard it said many times, most recently today, that operators have the closest relationship with their customers, one that should be better "exploited". It's certainly true there's a relationship that's being exploited — an abusive one with large incentives to break on my side. All I see are operators blocking the way between me and the application I really care about: The Internet. My closest relationship is not with them but my social network and these days they're on The Web, people who I know by name but not necessarily as numbers in my phonebook.

I think these anecdotes serve to illustrate why the thrust of my talk which is on the cultural rather than technical differences between IMS and Web 2.0.

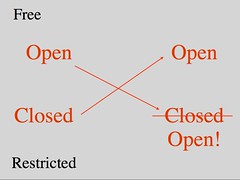

Matt Jones recently put together a great presentation entitled "The New Negroponte Switch" where he took Nicholas Negroponte's flipping of TV and Telephones from Wireless to Wired and vice versa to apply to products and services, examples being objects we currently hold dear such as cars becoming services, e.g. zipcar and services such as websites appearing as desirable objects. This flipping is a cycle, where there is money to made anticipating and taking the tack early. Listening to Vince a moment ago talking about Application stores I was motivated to sketch this slide: open and closed flipping. But it's a point I regret making because forever the optimist I believe everything is destined to become more open!

Speaking of being open, I like to use a back-channel at events like this where only one person can speak at one time, so looked on Twitter for people mentioning ETSI, but just some Greek and myself. I understand there is a chat.etsi.org, but I don't have a scooby what to do with an .exe file.

Anyway, the subject on the card is Web 2.0 …

… and we've two Tims to to thank for that: Tim O'Reilly, who coined the "2.0" term and Tim Berners-Lee, who invented the Web. Of course Timbl didn't actually build the Web. We all did that collectively! But it was him and a few notable grey-beards who provided the architecture of participation, enabling distributed extensibility, and from its heart offering great rewards for openness and concurrence. Timbl is a visionary, and having in no small part fathered the Web, has spent a number of years working on that difficult second album — The Semantic Data Web.

If Timbl knows where we should be be, Tim O'Reilly knows exactly where we are now, something he's able to do by assembling a formidable social network, which he brings together through publishing books and holding conferences, most exclusively the annual Foo Camp. Much of the substance of Web 2.0 comes from a series of books on social science, including The Wisdom of The Crowds and The Long Tail, and the fantastic The Cluetrain Manifesto in which BT's JP Rangaswami has a chapter in the ten year anniversary edition. Then there are books which post-date Web 2.0, but owe much to its culture, such as Everything is Miscellaneous and Here Comes Everybody and Black Swan.

I guess the odd one out is "Black Swan" with its warning that the next big thing is unlikely to be in the place you're looking, rather out there in the long grass. Disruption is indeed a clever girl!

I'm irritated by people saying "nobody knows what Web 2.0 is" when it's actually a carefully set-out series of astute observations on The Web in 2005, well documentsed in a single paper. The name isn't great, but it's one devised, trademarked and controlled by O'Reilly, and certainly more tangible and real than, let's say, "SOA".

Something else which irks me is when people say "Web 3.0", as if that actually meant something real, which we all agree upon. It doesn't, and we don't. I'm happy for language and ideas to freely evolve, but Web 3.0 isn't an evolution of Web 2.0, it's a subversion. We really need Versioning 2.0.

So it's The Web which is interesting, and not plays which are specific to a network or device. What the phrase "The Web as a Platform" actually means depends on your definition of a platform, but from my perspective it's an information architecture, populated with and by the people, and you ignore them at your peril!

One challenge to the notion of an open, free platform, independent of any device is the current success of the Apple iPhone store, which is predicated on a "trusted" path between Apple.com and that seductive, locked down device in my pocket. A device I'm unable to install my own software upon, let alone put my fingers into to hack or repair. This troubles me because whilst it's great to see such an vibrant ecosystem of innovations and toys and bedroom coders being paid money for software, that "trusted path" can never be trusted so long as it belongs to a single vendor. A multitude of per-vendor store-stove pipes isn't what we want to see either. So as the forever-open-optimist I suspect this is really a short term scenario, and something which will break down as more open alternatives emerge.

Not many people know it, but America has a machine which turns wheat into cars — it's called Japan. As engineers we like to employ engineering to solve problems, whilst mining the wisdom and madness of crowds is the solution to many of the hardest problems, for example recommendation: "people who bought that, also bought this" and other forms of "intelligence" where the reality is you're not dealing with a machine, rather a multi-person mechanical Turk. One of the nicest explanations of collective intelligence in the context of Web 2.0 is Michael Wesch's video, The Machine is Using Us:

Another favorite explanation of collective intelligence and Web 2.0 comes in the form of a rapid, dense and beautifully pretentious talk from Jeremy Keith — The System of The World which I'd highly recommend listening to:

I'm sure the phrase "Data is the next Intel Inside", must make our colleague from Intel very happy! Having mentioned the name, do I now need to hum the Intel sonic logo?

Web 2.0 companies are built upon data, and are very aware of which data they should give away, and what they should keep and capitalise upon.

Google spend a lot of money buying maps, something of a valuable commodity, which they then spend money publishing on The Web. This is a great service, one I quite often use whilst still logged into Google mail. Whilst I'm slightly unnerved by how much Google is learning about me and my map use, it's something I can live with in return for a better service. Of course if they betray our trust and weird us out, we'll stop using them! More recently we've seen entire Web 2.0 databases becoming freely available for download, for example Stack Overflow and Yahoo! Geo Planet, which I think highlights the point — the data isn't as valuable as knowing how people use it, either personally or usually more importantly, en masse. It's also in all our interests to see how people innovate with data. More on that in a moment.

Many people who haven't read Tim's paper think of Web 2.0 as being about company names without vowels, shiny logos, rounded corners and Ajax. As important as Web site design is, along with innovations in interactive Web clients, they are in essence simply other aspects of The Web as a Platform. Some see Flash, Silverlight or even JavaFX (yeah, right!) and think they're the future, when in reality they're little more than echos of the past. These closed blobs of binary are desperate last acts of lockin to development tools from vendors no longer in control. Flash is fine for natty games, but most RIA plugins lack the very features which made Web pages such a huge and immediate success: hyperlinking, cut and paste of simple text, no need for developer tools, ubiquitous clients and most important of all: view-source. Luckily Flash is increasingly becoming little more than a device driver, back-filling for features missing from the Web, a stop-gap while the winner emerges: the open evolution of HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

Perpetual beta and lightweight programming models, manifest themselves in sites which evolve before our eyes. In many ways this approach has become the new orthodoxy and anyone involved with software development can't have escaped the agile development movement. Many agile methodologies involve elevating The Customer into a position of despotic authority. This works well, where The Customer is a single person, usually the person paying for the development. Where it breaks down, is where The Customer attempts to represent a community of users for a product or service.

The above photo is from the Apollo 13 control centre, soon after hearing the famous words "Houston we have a problem". Here, small teams worked well to solve problems, and although the teams, often self-forming, behaved in an agile manor, it was one man's grand vision to have that moon-shot, and a hierarchy which made sure it happened according to plan.

All well and good, but not so if that one-man's vision and the apparatus of control are not working in the best interests of the community — misguided or misinformed, as as in Mao's Great Leap Forward?

Enter open source!

Clay Shirky gave a great talk at Supernova 2007 where he described a Shinto shrine, which although more 1,300 years old, was rejected as a Unesco world heritage site because it's made of wood, which not having the greatest longevity of building materials meant that the building couldn't possibly be that old. The monks knowing this, periodically ritually tear down the temple and rebuild it with wood gathered from the same forest. Clay points out how this is like open source projects who only exist due to their communities rebuilding their code each and every night, and whose detractors often don’t care that it works in practice because they already know it doesn’t work in theory. The rewards for participating in an open source project are not usually monetary, so Clay dubbed this new approach to collaboration: The Love Economy.

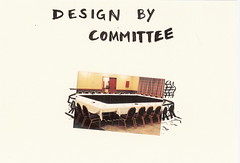

An alternative to empowering The Customer despot, is to form the collective committee. and engage in a spot of what is to all intents and purposes standardization.

But as my WS-* rant described, this can go badly, too and descend into Design By Committee, where the outcome is invariably a collection of options everyone hates the least.

There is little glamour and there are few rewards for participating in a committee. Possibly justifiably!

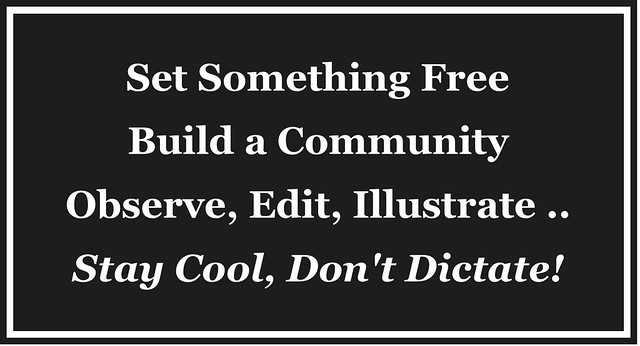

So, although I've just advocated against the despotic role of The Customer, most open source projects have such a person in control: the Benevolent Dictator For Life or BDFL.

However the big difference between The Customer and a BDFL is central to how open source functions. Most projects are driven by contributions, and it is the role of the BDFL to edit and exercise his design authority and taste in selecting which contributions become a part of the project. It's rare for someone to contribute code just for the heck of it, so contributions provide an excellent set of requirements. This is sometimes dubbed Itch Driven Development.

It's important contributors don't feel disenfranchised and are able to continue to use their contribution even if it doesn't become a core feature. For this reason most open source projects have good models for supporting extensions and plugins.

This feedback process is also employed in part by Web 2.0 companies who observe closely how their community of users behave, and use this practical experience to guide the direction of their service. Observation and editing of patterns exhibited in wild is also central to Web standards communities such as Microformats.

In the past, keeping an open source project together under a single repository was key to successful collaboration, and threats to fork a project would be a way of keeping a BDFL in check. In someways this cohesion is being challenged by the latest generation of distributed revision control systems such as git, which simplify and actively encourage forking code-bases. This additional freedom is already starting to change the dynamics of a number of open source projects. Interesting times!

Forking is also a challenge to Web 2.0 services, where competition is the control that keeps most services honest. Should, a service behave badly, everyone will quickly jump to another, better service. This is one of the new tenets of social networks: that they aren't "sticky" or tied to a single service: they are highly mobile.

Finally, let me end on something obvious, but very important. Call them new business models if you must, but closed and restrictive licensing is incompatible with open source. Unreasonable and discriminatory licenses such as RAND seriously limit the adoption of technologies on the Web.

So, in a nutshell, here is a tick-list for an architecture for participation:

- Open Source Implementations

- Test Suites

- Continuous Integration

- Wiki Driven Documentation

- Small, Lightweight Speciï¬cations

- Free and Open Licensing

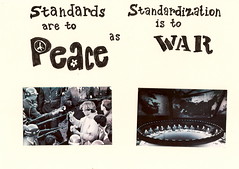

I've published a manifesto for this approach in the form of a gnomic sampler on http://standeace.com, a contraction of "Standards" and "Peace":

- How sustainable are Web 2.0 business models?

- If not a bubble, it does seem a little frothy out there, but open source and cloud hosting means investors can often afford be more patient and considered about their exit strategies. A clever Web 2.0 company will fully understand the economics of "free", and how to use The Because Effect. Upcoming hotness surrounds owning the canonical URL for a social object, for example Amazon being the place to link to for a book and Spotify vying with iTunes as the way of identifying a song. Then there are the likes of Twitter and FriendFeed, places to discover what's new and follow leads as and when things happen — new markets which have the potential to dwarf conventional search and news services.

- Without standardization of APIs, aren't the Web 2.0 companies behaving in restrictive ways?

- Heh, it is indeed possible that some of the new VOIP operators are capable of out-telcoing the telcos, and there is lockin, especially when you publish a photograph on Flickr or Facebook — the photo may still belong to you, but the URI and inbound links sure as heck don't. With many Web things there is a sense that each space has a zero-sum game with winner takes all, but we're starting to see more coming together with community initiatives such as OpenID, OAuth and layers above such as Google's Open Social which is now an independent organisation. Many people get excited about Data Portability and open APIs, but by far the best way to achieve portability on the Web is to host your own stuff on your own domain, something becoming easier with cloud computing and then there are naming services such as chi.mp, .tel and even ENUM, though all three of those approaches have issues and I'd advocate grabbing yourself a bog-standard DNS address. The reality is once a social network is established, it becomes easy to jump across services, so don't go thinking there's anything special about Facebook, it's just last year's Bebo.

- We have an IP TV service we're rolling out which our customers love. Isn't it consumer services such as this which this show how the Web will be replaced.

- In a way, you could say the same thing about the iPhone or indeed any other app store, but they're transitory stove-pipes and not the end-game. Regarding TV — in a world with abundance, where anyone can watch anything at anytime, what you actually watch will most likely be informed by your social network for those 'water-cooler moments'. I'd be surprised if all my friends use the same single service, so the Web is where we'll go to discover, research, bookmark, rate, review, and share what we've all been watching.

- The industry is currently rolling out broadband and fiber and if there is no great return on the investment, it will stop!

- I'd certainly pay a premium to have fiber to my house, but if you extort me by the megabyte, then I'm highly motivated to route around you and collectively we'll build an ocean around the guild built canals. If broadband is fundamental infrastructure which like sewerage systems we need everywhere, then there's a greater role for governments c.f. The Digital Britain Report.

- If things are free, how do people like artists and film makers make money?

- Big changes are afoot: old world shops needed best seller lists to help decide what to physically stock, whilst Amazon apparently makes more money from the long tail, allowing more people to make a profit than just the lucky few. The social Web means good stuff will still bubble up to the top only it's stuff more relevant to you. OK, that's a babbling way of saying there's a lot more stuff available, and much of it is becoming free. These changes in abundance and cost disrupt business models, but it's a disruption that's happening, so it's up to us all to learn to deal with it! I don't know how this will pan out, and I suspect nobody does, yet, but I'm positive together we'll figure it out.

- If we make a mistake and expose customer data, the regulator kicks us, and yet if you put your credit card details somewhere silly on the Web, it's your fault. Isn't that unfair?

- The answer is in your question: telcos typically like to own customer data, I understand in Japan where by law every mobile has GPS, operator restrictions means a local application usually has to request the device location from network, which polls the device and then passes the result back to the phone! Other traditional mobile services involve an operator polling for a cell-phone's location to send a taxi, pizza, etc. often at a high cost to the customer or the service. On the iPhone, the customer has direct access to the API which they can use locally or pass to a Web 2.0 site such as FireEagle, Dopplr or Tripit. These services manage sending location a their social network and other devices using permissions models which are transparent and easily understood by the user, be that precise coordinates, an approximate region or a complete lie. In brief: put sensitive information and its control firmly into the hands of the customer!

I felt bad and had been possibly a little too rude to my hosts, so admitted to having an alter-ego who attended Web conferences to extol the value of phones concluding: GSM is cool. Fibre to the home is way-cool. Please keep doing that! APIs and IMS? Um, not so interesting! The pain points ahead for the Web are video streaming which will introduce new kinds of bottlenecks and Web friendly messaging and eventing. Build us a great infrastructure, a strong architecture of participation from which we are all free to innovate upon, using The Web, and from the edge of the network.

Over dinner I was luckily enough to engage with some of my more robust inquisitors, and had some great conversations around privacy and the economics of open with some formidably smart people. Just as I was retiring, shaking hands with my combatants, I was left with "as much as I enjoyed your presentation, I didn't understand a single word", and "I looked at your Twitter, what a load of rubbish!" both of which made me laugh like a loon. Oh well, I may not have saved The Empire, but I had fun trying.