Herein, my talk for last night's Ignite London #4, a really well organised global event with a parade of great speakers, each presenting for 5 minutes against a deck of 20 slides which transition automatically every 15 seconds.

In the event I was quite nervous, and felt my talk could have benefited from more rehearsal. Below is how I would have liked to have delivered it.

I intended to talk about I-Spy books, a publishing phenomena from 1948, and why it has such a disproportionally small footprint on today's Web, but in preparing these slides I found myself reverting to type. This talk is about The Web.

Standing before you, I would like to think I exemplify that old adage that growing old is mandatory, however growing up is optional. I'm fine with being seen as child-like because it's the childish motivations of curiosity, collecting and sharing which fuel The Web.

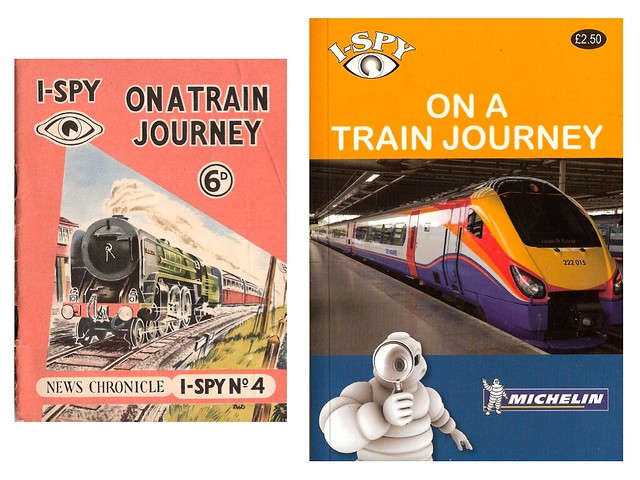

My abiding childhood memory is of being bored. Bored beyond the estimation and comprehension of my own children, growing up surrounded by a ubiquitous variety of consoles, hand-held games, iPods, and on-demand television. Nowhere was this boredom more apparent than on a long train journey. Luckily my mum would often buy an I-Spy book, giving me a a pocketable compendium of interesting things to look out for along the way.

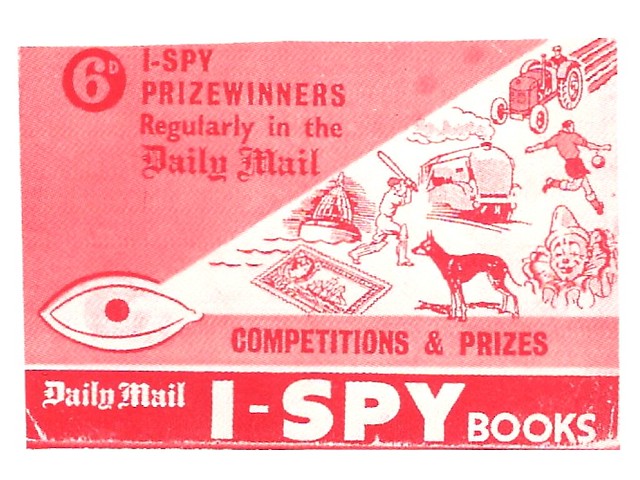

I-Spy books were very affordable, they were 6d for nearly 20 years, before decimalisation and the subsequent hyper-inflation. In 1970, 6d would buy three packets of crisps. The current editions are £2.50 or about five packets of crisps. Judging by their size, pocket sizes have also increased over the years.

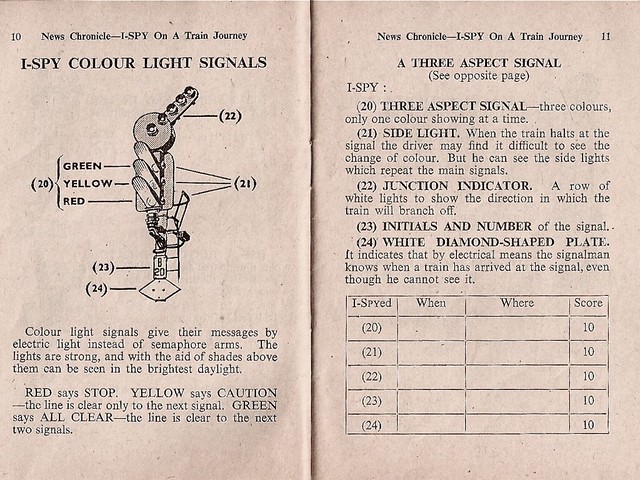

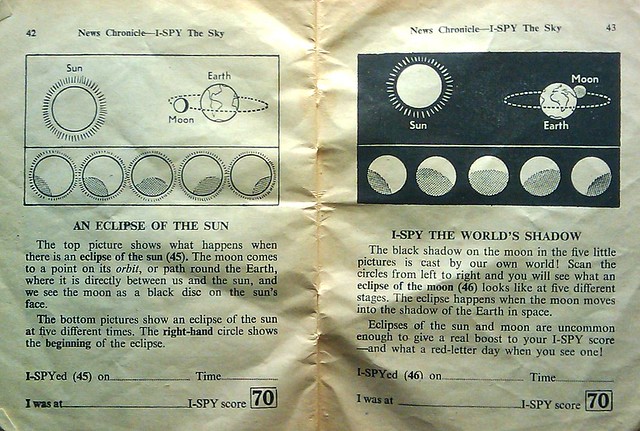

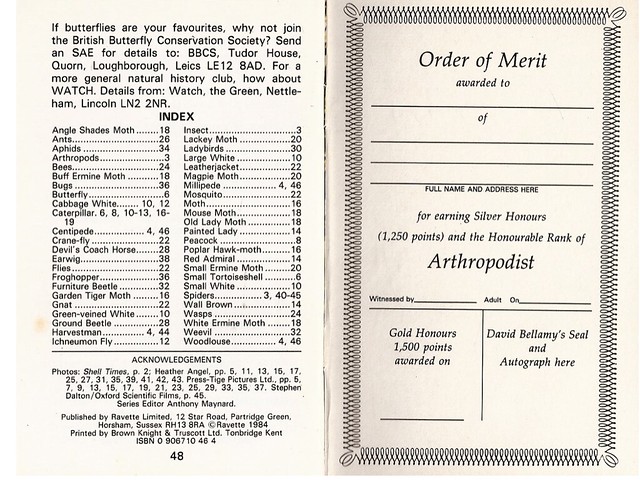

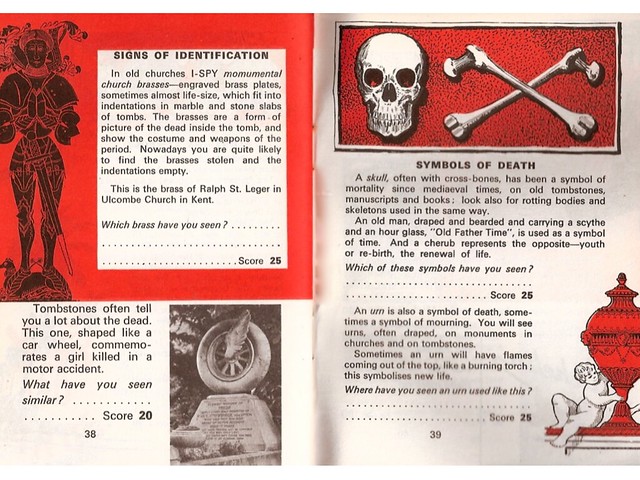

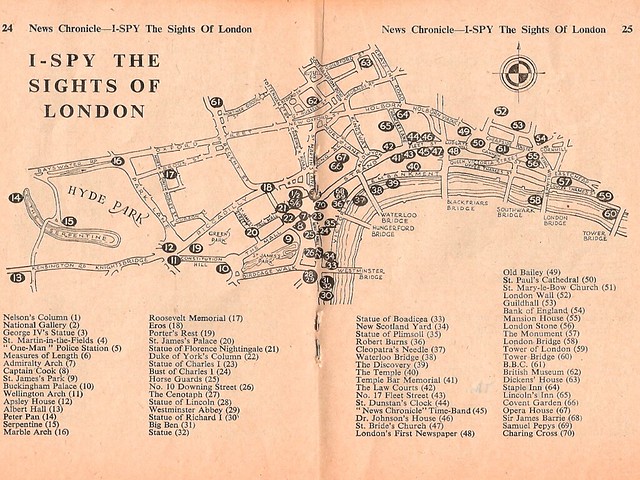

Here's a typical 1950's I-Spy book. Every page crammed with detail, beautifully presented even though it looks as if it was made on an office typewriter. The owner is given a list of items to find and record the date and their location in a table.

I learnt a lot from these clear explanations, but always felt the point system unfair, especially growing up as I did in a small provincial town in north east England. The nearest set of traffic lights were six miles away and the chances of having a ‘red letter day’ and seeing a full eclipse of the sun [70 points] during the 1970s practically zero. Interesting things are very unevenly distributed.

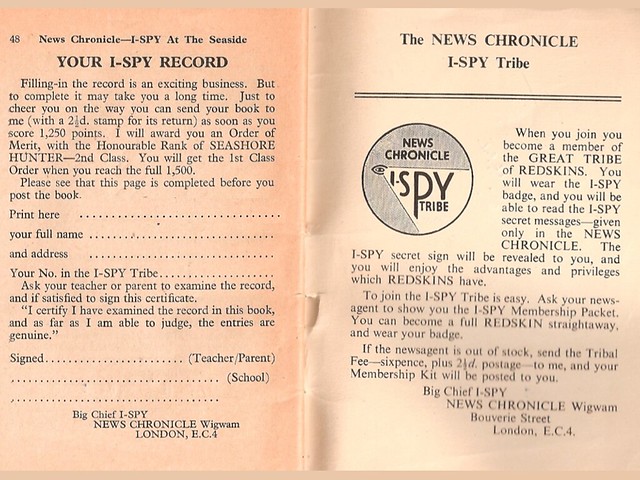

Having collected enough points, the completed book was signed by a trusted party, a parent or teacher, and sent to Big Chief I-Spy, at The Wigwam by The Water, a retired headmaster in an office off Fleet Street. Cheating was highly frowned upon. The original Big Chief I-Spy, Charles Warrell retired in 1956, but lived on until 1995 when he died at the age of 106.

In a time before computers and calculators, I-Spy books served as training for the anticipated world of work, a place populated by paper technology: logarithm tables, memoranda of understanding, log books, round-robbins, slide-rules and volvelles.

Being enlisted as a member of a club was how to get on in this world. It's fun to be in the know, to be that geocacher hiding secrets in an Altoids tid magnetically attached to the back of a notice board, passed by muggle-commuters or part of the rarified gang of early twitters or one of the Quora elite, basking in your own undiscovered corner of The Web before being discovered by the great unwashed bringing their Social Media Smallpox.

But every good story has its dark side, and you can imagine my feeling on discovering I-Spy was once owned by The Daily Mail was akin to discovering Beck is a Scientologist. News Chronicle, a newspaper founded by the Cadbury family, and who fought Franco was diametrically opposed to their new right-wing owners.

The same concerns face us now on The Web: the possibility of Microsoft buying Flickr before we realised the deletionistic Yahoo! were more than capable of ‘sunsetting’ our delicious data by themselves, tossing our memories along with our trust to join geocities in that great 404 in the sky, or learning the BBC Website is now managed by day-zeroist vandals who want to render thousands of URIs unresolvable, or worse possibly resolve to something completely different, removing our contributions to community endeavours, tearing apart millions of our inbound links, the very fabric of The Web only to make a few disks spin faster and give them more cash to make more episodes of Cash in the Attic.

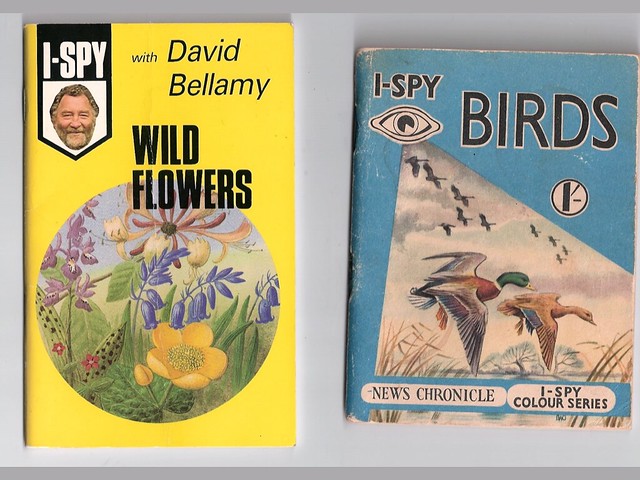

Luckily the days of The Mail didn't last long, and the books of the 70's continued to be quite lovely, continuing to appear to have been produced in a small reprographics shop, cut and pasted on a photocopier.

The books from the 90s, with David Bellamy are worth collecting, pocketable, affordable versions of Thorburn's Birds or The Concise British Flora and Fauna.

I was quite excited hearing I-Spy are now published by Michelin, given how much I love their Green Travel Guides which exude quality typography and applied semiotics

However true to form, modern I-Spy books are made using office tools of the age, these smell of Microsoft Office, word-art and colour schemes only an enterprise could love. At least we're spared Comic Sans.

They're printed on awful glossy paper, making them smudge, the certificate has a serial number, I guess as pretend DRM, so much for the code of honour, and instead of Big Chief, we have a corporate logo, the Michelin Man. Sigh.

So what should an I-Spy of today look like? Well there's the obvious SMS game of Yellow Arrow or mobile games of noticin.gs and fousrsquare but really there are dozens of places engaging our compunction to collect data. I know people who build the likes of dopplr.com and Lanyrd are cool, with the best of intentions, but these sites are nothing without our data, and yet it's clearly no longer our data thanks to unclear licensing and barriers to exit. They're commercial entities with no immunity from The Daily Mail effect.

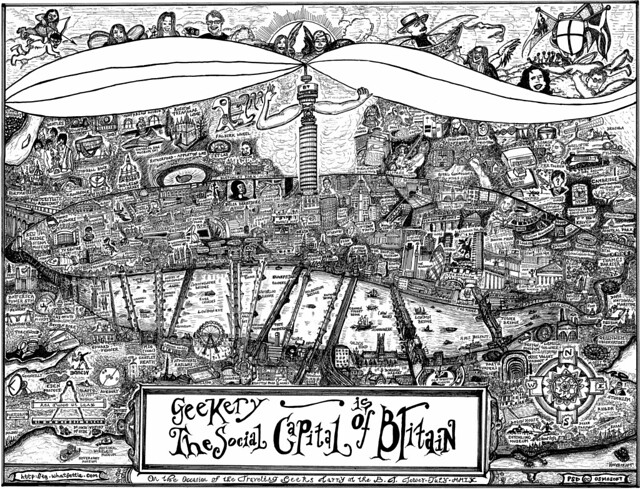

My own, modest I-Spy like offering is a hand-drawn map of Britain, a collection of geeky points of interest. It's released under a Creative Commons License, has been copied many times making it safe for me or indeed anyone else to build upon in the future.

So my plea is to engage your inner I-Spy, create interesting collections, but be careful where you put them and beware of The Daily Mail!